Foreword: On Football and Mothers

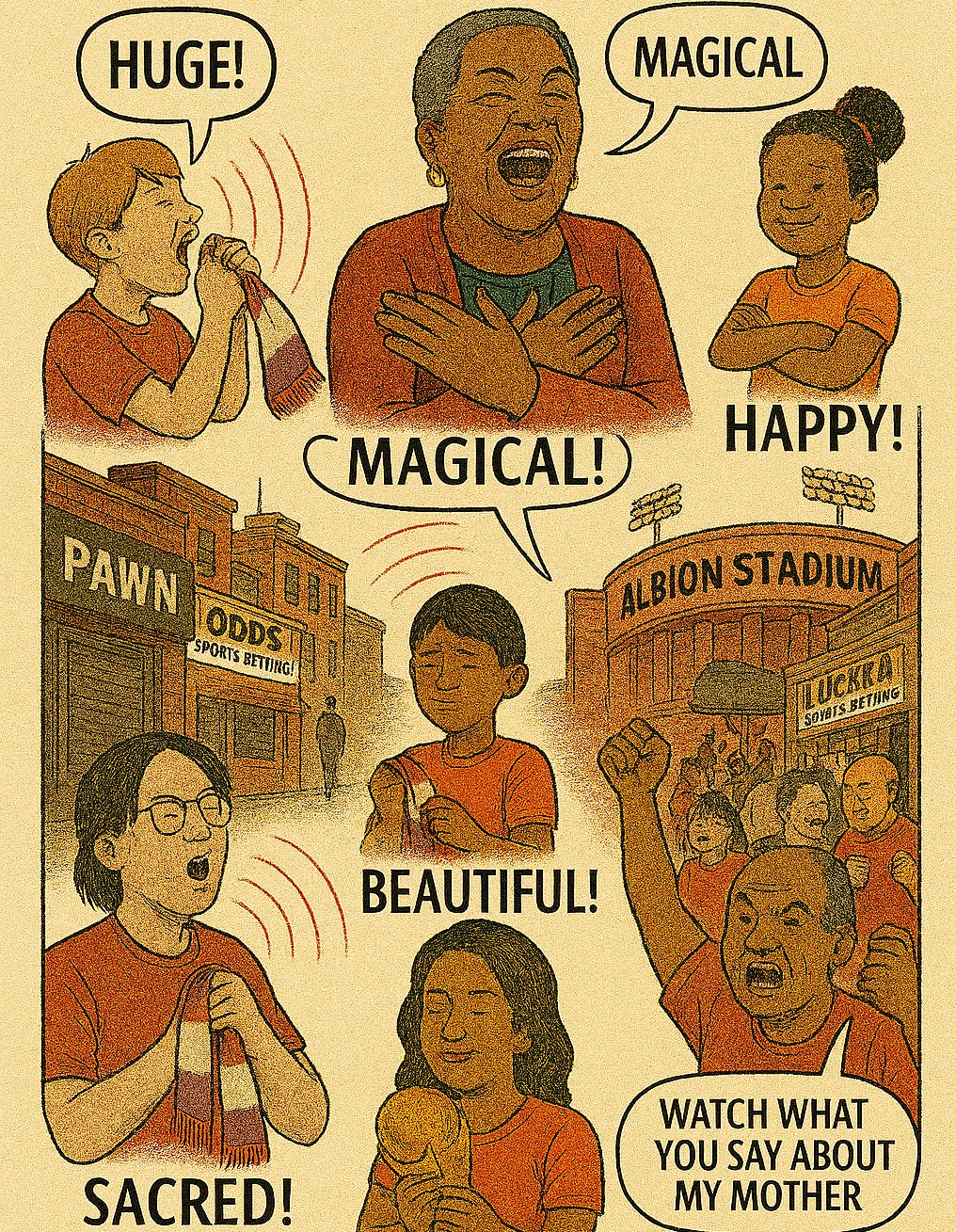

For most people in the world, football is the most important of the least important things. It represents identities and ways of understanding the world to millions of people. This means that talking about football is like talking about one’s mother. You better be careful what and how you go about it.

So what possessed two reasonable strangers to sit and talk about this potentially volatile topic? They could’ve spoken and written about much lighter, less volatile issues like politics or religion.

Why? Are you serious? Nothing explains humanity like football does. That’s why!

That’s why two perfectly reasonable people from two opposite corners of the world have chosen to make a case, from their perspective, for what makes a club big. For this exercise, each of us decided to pick our own KPIs. After all, who are we to tell anyone what qualifiers to use to describe their mother?

We are not being lazy. We talked about this. We just couldn’t come up with the right measurable. Instead, we will present our argument and share with you our final conclusion.

What Makes a Big Club? Kwame Twumasi-Ankrah’s Perspective

The Ecosystem Big Club: When a Team Is Not Chosen, But Inherited

In Accra, no one decides to support Hearts of Oak. You’re born into it: like your name, your neighborhood, or your first language. Your grandfather bled red, yellow, and blue. Your uncle skipped school to watch the 2000 CAF Champions League final. Your barber closes early on derby days, not for business, but for ritual. This is not fandom. This is kinship. And it’s this irreplaceability, not revenue that defines a truly big club.

“Bigness” as Belonging, Not Branding

In the global North, “big clubs” are often measured by how far their logo travels: jerseys sold in Jakarta, pre-season tours in Las Vegas, social media followers in the millions. But in cities like Kumasi, Lagos, or Alexandria, a club’s size is measured by how deeply it’s woven into the social fabric – so deeply that its absence would leave a tear in the community’s sense of self.

Ask a Kotoko supporter in the Ashanti Region if his club is “big.” He won’t cite trophies (though they have many). He’ll most likely say:

“When a fellow fan and colleague of mine passed away, the club paid a heartfelt tribute to his memory with a vigil at the stadium. This club is like my second family.”

That’s not marketing. That’s membership.

A big club, in this sense, isn’t one you follow. It’s one you belong to like a church, a clan, or a hometown.

Survival as Proof of Greatness

While European giants fret over Financial Fair Play (FFP) and balance sheets, African “big clubs” often operate in conditions of structured scarcity:

Unpaid player wages

Stadiums with broken seats and no floodlights

Boards riddled with political interference

Yet they endure. Not because they are well run, but because they are necessary. Hearts of Oak went nearly two decades without continental success. Yet on matchday, Accra still pulses red, yellow, and blue. Kaizer Chiefs haven’t won the league since 2015, but Soweto still shuts down when they play Orlando Pirates. Why? Because these clubs provide continuity in chaos, pride in hardship, and collective identity in places where the state often fails to deliver. That kind of resilience cannot be engineered by a CEO or funded by an oligarch. It’s grown organically, messily, and stubbornly over generations.

The Mythology Money Cannot Buy

Manchester City can spend £1.5 billion and win a Champions League. But can they produce a song that echoes through minibus taxis from Tamale to Takoradi? Can they inspire a mechanic in Nima to name his shop “The Phobians Auto Care”? Can they make an 70-year-old-woman in La weep when they lose not because of the score, but because it feels like the city lost its voice?

No. Because mythology is not purchased; it is lived. Real “bigness” isn’t about how many people know your club. It’s about how many people need it to feel whole.

Global Echoes of Belonging

This logic of irreplaceability is not confined to Africa. It echoes across continents–in Japan, South America, and beyond–where clubs are not brands to be exported, but identities to be inherited.

In Kashima, a quiet city and its surrounding five towns with a population of fewer than 300,000, football is not imported. It is homegrown. Kashima Antlers, founded in 1947 as a works team for Sumitomo Metal Industry, have never been relegated since the J.League began in 1993. They are the most decorated club in Japanese football history, with eight J1 titles and 35 domestic and international honors. Their stadium is more than a venue. Locals call it a temple of Japanese football. When the 2011 earthquake devastated the region, the club temporarily relocated but returned with a mission: to rebuild not just a pitch, but community spirit. The Brazilian legend Arthur Antunes Coimbra, known worldwide as Zico, arrived in 1991 and scored a hat-trick in his first match. In Kashima, he is not called Zico. He is called god—not out of worship, but because he helped forge a culture of excellence that endures. This is not a club that moved to a city. It rose from one. And that is why, without oil money or global branding, Kashima Antlers remain irreplaceable.

In Buenos Aires, Boca Juniors is not chosen. It is inherited. Founded in 1905 by five sons of immigrants in the working-class port neighborhood of La Boca, the club absorbed the resilience of Genoese dockworkers, Polish tailors, Turkish merchants, and Jewish families who built their lives along the Riachuelo River. La Bombonera is more than a stadium. It is a gathering place where generations mark life’s milestones—first games with fathers, celebrations after exams, vigils after loss. When Diego Maradona walked its corridors, he was not a global icon. He was one of them. When Martín Palermo missed three penalties in one match, fans did not abandon him. They sang louder. This loyalty is not transactional. It is ancestral. Boca has won titles, yes, but its greatness lies in how deeply it is woven into the identity of a people for whom football is not an escape, but an expression. If the club vanished tomorrow, a part of Argentina would lose its voice. That is not fandom. That is belonging.

River Plate represents a factory of dreams rooted in discipline and vision. The club, located in the Núñez neighborhood, has achieved a record 38 domestic league titles and established one of South America’s most prestigious academies, La Escuela de Fútbol. From Alfredo Di Stéfano to Enzo Fernández and Julián Álvarez, generations of talent have passed through its gates, with most making their first-team debut before turning 18. The club’s philosophy is clear: identify talented kids as early as possible–perhaps as young as five–and develop them through an organized, possession-based system that emphasizes technical proficiency, tactical understanding, and character. Led by figures like Gabrielle Rodriguez, who has been nurturing the academy for decades, River Plate views player development as education, not just sport. But its graduates contribute more than just to European rosters. They are the cornerstone of Argentina’s national team, with six players from the 2022 World Cup squad having been honed in the shadow of the Estadio Monumental. River Plate’s greatness is not imported. It is cultivated, patiently and precisely from the soil of its own city. That’s why the club has proven irreplaceable, even as its stars depart–not as a brand, but as a builder of legacy.

América de Cali in Cali, Colombia, is not just a football club. It is the heartbeat of a city known as the “Sultana del Valle.” Under its legendary manager Gabriel Ochoa Uribe, a former goalkeeper turned disciplinarian tactician, the club entered its golden age in the 1980s, winning five consecutive league titles from 1982 to 1986. But their greatness was never just about trophies. It was about identity. Known as “The People’s Team,” América wore red not as a brand but as a banner of working-class pride. Players like Willington Ortiz, Luis Eduardo Reyes, and Roberto Cabañas were not just stars — they were local heroes who embodied resilience, discipline, and collective purpose. Even in years without continental success, the club was one of the cornerstones of community life: its matches were weekly rituals where generations went together to reaffirm who they were. América de Cali has been a club ravaged by relegation, financial hardship, and political turmoil, and it prevails. And not because it was designed to win, but because it was born to belong.

In Santiago, Colo Colo isn’t only Chile’s most successful club. It is the emotional compass of the nation. The club, founded in 1925 by David Arellano, was built on the premise that football could bring a divided society together. It has never been relegated — a record in Chilean football — and in 1991 was the first and only Chilean team to win the Copa Libertadores. But its metrics go well beyond trophies. Colo Colo operates as a national institution with about 42% of the country identifying as fans (according to estimates). Its black-and-white stripes are worn not as fashion but as a family crest. When the club plays, whole neighborhoods grow silent. And when it triumphs, strangers hug in the streets. Even during social unrest and pandemic lockdowns, the club sustained its social ties with its fanbase. They extended season tickets free of charge, not as a business decision, but out of loyalty. This is not a marketing brand for export. It’s also a home born of history, adversity and collective memory. And this is why Colo Colo is irreplaceable, even in the absence of global tours or billionaire financing.

The Global Stage as Home Ground

This ethos was on full display during the 2025 FIFA Club World Cup, when Brazilian clubs were not only competing, but proving that greatness in football is more than balance sheets. It’s all about presence, pride and collective will. Fluminense, Flamengo, Palmeiras, and Botafogo–four representatives, moved beyond the group stage. They turned the stadiums into extensions of their home neighborhoods. Botafogo stunned Paris Saint-Germain, the reigning European champions 1-0 in a game that sent ripples from Rio to Recife. Fluminense went furthest of all, becoming the only South American club to reach the semifinals. They were powered by local talent and the return of veteran Thiago Silva who returned not for a final payday but to close a chapter with his boyhood club. Even in defeat, these teams bore the burden of cities, not shareholders. A few of their players may have left for Europe, but they exceeded expectations with their presence and brilliant team performances. That is not branding. That is belonging.

And it is not only South America. Al-Ittihad, Al-Hilal, and Al-Sadd have each carved distinct paths in the FIFA Club World Cup, representing Asian football on the global stage with varying degrees of success. Al-Ittihad made history in 2005 by becoming the first Asian team to reach the semi-finals, narrowly losing 3-2 to São Paulo before falling to Deportivo Saprissa by the same score in the third-place match. Their 2023 campaign, as hosts, ended in the second round with a 3-1 defeat to Al Ahly. Al-Hilal stands out with the highest finish among the trio, reaching the final in the 2022 edition held in Morocco. After a dramatic 3-2 victory over Flamengo in the semi-finals, they lost 5-3 to Real Madrid in a high-scoring final. Al-Hilal also secured fourth place in both 2019 and 2021 and reached the quarter-finals in 2025. Al-Sadd’s most notable performance came in 2011, when they finished third. After a heavy semi-final loss to Barcelona, they defeated Al Ahly on penalties following a goalless draw in the third-place playoff. Each club’s journey reflects a different facet of ambition, resilience, and regional pride in the evolving narrative of Asian football.

The True Test of “Bigness”

So here’s a litmus test, one I’ve used as a fan and observer through the streets of Accra:

“If this club disappeared tomorrow, would the city feel orphaned?”

For Hearts of Oak? Yes.

For Asante Kotoko? Yes.

For Al Ahly in Cairo? Yes.

For Kashima Antlers? Yes.

For Boca Juniors? Yes.

For River Plate? Yes.

For América de Cali? Yes.

For Colo Colo? Yes.

For a club propped up by oil money or billionaire ego? I feel the tourists would move on. The investors would pivot. And the players would sign elsewhere. But in Accra, who would close the shop early on Sunday? Who would gather under the mango tree to replay the match in memory? Who would teach their grandchildren the chants? A big club is not the one with the shiniest stadium or the fullest trophy cabinet. It’s the one that, even in ruin, remains irreplaceable. And that kind of bigness cannot be built; it can only be belonged to.

What Makes a Big Club? Edwin Canizalez’s Perspective

Two words: Real Madrid

Look, I’m a romantic. My favorite times are RCD Espanyol, Atletico de Madrid, UP Plasencia, and Hercules CF (To be clever, I’m not allergic to winning). But by any measure we could use Real Madrid as the embodiment of a big club because by all definitions it’s the biggest one, ever. RMA would excel in all the boxes above as top. If we went with that, we could talk about how it got there, not throughout history but in recent history under the Perez presidency. He implemented the Balanced scorecard approach and put the team back on the map.

That would help us distinguish between a historic club, rich clubs, and a big club. There are tons of historic teams that have never won a trophy, but had great managers; or were not wealthy but conquered great heights in competition. Or lately, there have been clubs that had spent tons of money but their current business model is not sustainable. For example Manchester City and PSG: MC spent about 1.5B throughout several seasons to win one champions league cup. That is a negative net earnings of -1B BGP. PSG has a similar story. Also, these teams are at the mercy of their team owners who fund these clubs via oil money. And just like oil, their interest will run out. They are not fans, they are investors; and by that nature, they have to be smart about how much money they burn.

RMA as Strategic Infrastructure

Real Madrid isn’t just a football club. Let’s be clear about that from the start. It’s a living system, part entertainment engine, part brand ecosystem, part strategic experiment in how identity, solvency, and spectacle can fuse into something that transcends sport itself.

Think of it this way: you’re sitting in a restaurant in Madrid at 2am, and the waiter who’s seen everything leans over and tells you that Florentino Pérez didn’t just buy a football team. He bought a religion and tried to run it like Goldman Sachs. That’s the story. That’s what we’re trying to understand here.

The Myth Economy

Pérez inherited Madridismo, not just a fan base, but a behavioral code. Elegance in victory. Dignity in defeat. A sacrificial ethos that somehow fused talent with humility. It’s the kind of thing that sounds beautiful in Spanish and suspicious in English, but it matters. It’s institutional DNA.

This is a classic tipping point problem: how do you take something inherently irrational (sports fandom) and systematize it without killing what made it magic in the first place? The mission was audacious: become the team of the 21st century. Not just through trophies, but through solvency, spectacle, and global resonance.

The thing about endurance sports, and I say this having done more ultras than is advisable, is that you learn systems thinking through suffering. You can’t just “want it more.” You need nutrition protocols, sleep architecture, recovery rhythms. Real Madrid applied that same logic to football club management. They built a Balanced Scorecard not as bureaucratic theater, but as a metabolic map.

The Architecture of Greatness

Here’s where the strategist in me gets interested. Because what Pérez built wasn’t revolutionary in concept. It was revolutionary in execution. Five interlocking systems:

Sporting Performance became predictable alchemy. The “Zidanes” and “CR7s” (global icons), “Pavones” and the “Carvajals” (homegrown talent), and “Intermediates” (stabilizers) weren’t just player categories. They were a portfolio strategy. Recruitment became brand logic. Coaching became cultural transmission. You weren’t just building a team; you were curating an emotional product.

Financial Solvency operated on a simple principle: income exceeds expenses, always. But here’s the trick. The club functioned like a content studio producing daily spectacle, not seasonal campaigns. Every training session, every press conference, every Instagram post was inventory. The stadium wasn’t a venue; it was a content production facility.

Brand Expansion treated the club as a global media asset. Audience size, engagement frequency, socio-demographic reach became metrics of value. Marketing shifted from passion to monetization, which sounds cynical until you realize that passion without sustainability is just a slow bankruptcy.

Infrastructure Modernization manifested as physical strategy. Stadium upgrades. Training facilities. Real Madrid City. These weren’t cosmetic. They were symbolic declarations. Selling the old training ground to cancel debt and building a new one ten times larger? That’s not renovation. That’s narrative.

Fan Experience recognized that excitement could be engineered. Spectacle became product. Fans didn’t just watch. They consumed, participated, affiliated. It’s the difference between attending church and joining a movement.

The Feedback Loop

There’s a moment in every great restaurant kitchen, and I’ve stood in enough of them to know, where you realize the menu isn’t just food. It’s theater, autobiography, and economic model simultaneously. Pérez understood this.

Signing Figo, Zidane, Ronaldo, Mbappé, created a feedback loop: excitement → merchandise → sponsorship → solvency → more icons. The brand became self-reinforcing. José Ángel Sánchez reframed the club as a content generator where emotional engagement translated directly into economic return.

This is where the novelist in me sees the tragedy brewing. Because in fiction, hell, in football, the moment you can explain everything is usually the moment before it all collapses.

The Wage Structure as Social Contract

Players were paid not just for performance but for brand contribution. Individual image rights were purchased to align salaries with revenue impact. The squad became a portfolio. Each player: a media asset. Each match: a monetization event.

Think about that for a second. You’re Zinedine Zidane. You’re not just paid to play football. You’re paid because your face moves merchandise in Jakarta and New York City. Your salary is a function of your global emotional resonance. It’s simultaneously brilliant and deeply weird.

The bench became a dream destination. Salaries were equalized to prevent rivalry. The only differentiator: image performance. Playing for Madrid meant shared responsibility, global exposure, symbolic elevation. It was communism with better suits.

Why Systems Fail: The Human Remainder

Here’s what the ultramarathon teaches you: perfect nutrition, perfect training, perfect everything, and then at mile 80, your body just says no. Because you’re not a machine. You’re a human trying to act like one.

Pérez built a coherent economic model. But his downfall came from ignoring the emotional and tactical core of the sport. The rupture of the Casillas, Hierro, Makelele, Raúl axis dismantled the team’s soul. It’s the moment when the system builder forgets that football isn’t rational. It’s tribal, emotional, fundamentally about belonging. You can’t spreadsheet your way into love.

Strategy without humility became hubris. The club had infrastructure, solvency, spectacle but lost cohesion. Pérez resigned not because the system failed, but because he refused to listen to the system’s emotional logic. He had all the ingredients but forgot the recipe is partly about instinct, partly about feel, partly about things you can’t measure.

What Endures

In central banking, people talk about “credible commitment,” the idea that institutions derive power from believable promises about the future. Real Madrid’s greatness wasn’t built on trophies alone. It was built on a strategic fusion of brand, solvency, recruitment, and spectacle that created credible commitment to excellence.

But here’s the thing about tipping points, about endurance, about any great kitchen or institution: the magic happens in the gaps between systems. In the moments of improvisation. In the recognition that measurement enables artistry but can never replace it.

The Balanced Scorecard becomes more than a tool. It becomes a map of institutional mythmaking. Pérez’s legacy is both blueprint and caution: greatness requires coherence, but coherence without humility fractures. Systems enable greatness, but greatness transcends systems.

You can engineer excitement, but you can’t engineer soul. You can measure engagement, but you can’t manufacture meaning. The beautiful game remains beautiful precisely because it resists complete systematization because there’s always a Zidane volley, a Sergio Ramos header, a moment that makes the spreadsheet irrelevant.

That’s what makes a club great. That’s what makes anything great. The courage to build systems while remembering that the system is never the point. The spectacle is never just spectacle. The myth was real all along.

So, What’s The Verdict?

What makes a club big? It’s as hard a question as why is your mother the best mother in the world. It’s so personal. So tribal. So familial. We can only agree on one thing: love.

What makes a club big is the collection of all the good, the bad, and the ugly about humanity. It’s the reason people get out of bed, and the driver of the excitement or sorrow the night after the game.

Tell us what you think. But remember, watch what you say about our mothers.

Like this piece?

If this piece holds, consider sustaining the signal: subscribe to Pattern of Play and Against Reduction, pledge, buy me a cup of coffee, or fund the next dispatch however you see fit. Every act of support helps metabolize the noise and keep the infrastructure unfinished but alive. Repost if it threads utility. Share if it exposes contradiction. Let it circulate where it’s needed most.

Really enjoyed this piece and reading the two varying perspectives!

Football is more than a game; it’s life lived in colors, chants, and loyalty. A big club isn’t defined by trophies or money, but by the hearts it claims, the communities it binds, and the passion it ignites. From Accra to Buenos Aires, from Kashima to Madrid, true greatness grows where belonging outweighs ambition, where soul outshines strategy, and where love becomes identity.